By Vicky Jassey

September 30, 2025

This is a long-form version of an article published by the Smithsonian. Additional material to the published version primarily begins with Cárdenas and the Birth of Añá in Mexico.

Haz clic aquí para leer este artículo en español.

Over the last twenty years, the Cuban Yoruba-derived spiritual practice of Santería and its music have exploded in Mexico. Mexico City—once the vibrant centre of the Aztec Empire, until it was violently overtaken by Spanish conquistadors in the early 1500s—is now the hub of a growing religious phenomenon.

Although there are no official figures—Santería is not included in the national census—Óscar Méndez, a professional ritual musician who has been part of the Mexican Santería community for over thirty years, recalls that in 1987, when he began drumming in ceremonies, there was only one tambor (religious drum ceremony) a month, with just three or four Mexican santeros (initiates) in attendance. Over the last ten years, however, he said, “the religion has grown like wildfire.” He estimates the number of initiates in the city in 2025 will be around one million.

In the religion of Santería, to become fully initiated, one must be presented to Añá, the Yoruba deity believed to reside within the three consecrated, double-headed drums known as batá or fundamento. Añá, through the sonic waves created by ritual musicians, acts as a portal through which humans can communicate with deities known as Oricha.

The burgeoning community of santeros in Mexico has led to an unprecedented demand for ritual musicians called Omó Añá (“child of Añá”), men and boys initiated into a male, heterosexual drumming cult who serve the religious community. Driven by a love for the profound and complex music of the Orichas, combined with the opportunity to earn a comfortable living, omó Añá have been arriving in droves from Cuba over the last twenty years or, like Méndez, have been homegrown in Mexico.

I want to explore why Mexico has become such fertile ground for this kind of religious expansion. What motivated a leading politician to facilitate the arrival of sacred drums in Mexico? What is life like today for professional ritual musicians working in Mexico City? And, finally, why do some associate Santería with criminality in Mexico?

******

Entering Mexico’s Ritual Soundscape

My interest in writing about the batá tradition in Mexico began in 2015, after hearing stories from two friends working as professional ritual drummers there: Antoine Miniconi from France and Dionisio Alzaga Cortés from Mexico. Both described a vibrant and growing religious-musical community that offered them abundant work.

Most of their accounts reflected what one might expect from a typical Santería ceremony—drumming, singing, dancing and occasional spirit possession, often culminating in an uplifting and deeply spiritual musical experience. Yet there was a striking exception: both had performed at ceremonies where a lion had been sacrificed—a startling indication that the religion was being practised in ways distinctly different from its Cuban origins.

At the time I heard their stories, I had already spent fifteen years studying batá music and singing in occasional ceremonies and had just begun research for a PhD on batá drumming, gender, sexuality, and change in Cuba (Jassey 2019). Naturally, I was intrigued to learn more about Mexican Santería, the role of batá drumming within it, and the sacro-socio-political conditions that led to lions being sacrificed during musical ceremonies.

In January 2025, I travelled to Mexico with my partner, David Pattman—a British omó Añá—to stay with Miniconi and his family. Miniconi no longer works as a batá musician, but thanks to him, we had the privilege of meeting some historic figures from the Mexican Santería musical community, attending and performing in ceremonies, and gaining a rare glimpse of an emerging part of Mexican Santería culture rarely witnessed by those outside of it.

On our first day in Mexico City, we raced through the city on our way to our first Mexican tambor de fundamento (musical rituals using consecrated batá drums). We were invited by the internationally renowned Cuban batá drummer “Piri” Manley López, who moved to Mexico City in 2013. To me, López is batá royalty. He was featured on many of the recordings I had listened to obsessively when I first began learning batá music. That day, he greeted us like old friends and opened the door to the world of sacred batá drumming in Mexico.

January 26th, 2025: Huehuetoca, Mexico City.

It was a beautiful day. A large marquee had been erected in the car park in front of a row of modest houses. We were invited into a small room to watch the oru seco (a ritual drum-only recital) performed before a shrine in honour of the Oricha Oyá. The recital was virtuosic and, at times, explosive, with Nereo Herrera on the iyá (largest drum), López on the itótele (middle drum), and “Astor” Alfonso Toro on the okónkolo (smallest drum).

López, Herrera and Toro play the oru seco. Video by Vicky Jassey. 26th January 2025

I learned that the purpose of the tambor was to “present” seven iyawós (“bride of the Oricha,” or newly initiated devotee) to Añá. This musical ritual would complete a crucial part of their initiation. Vitia Valdés’ voice, leading the call-and-response chants, cut through the air. Accompanied by the drums, he sang through the oru cantado (a recital accompanied by songs and salutations). The atmosphere was buoyant as the congregation chorused and danced, their response alive with an energy both ancient and timeless.

As we moved into the main section of the ceremony, “Martincito” Martín Silva, a babalawo (priest of Ifá), drummer and owner of the fundamento, invited me to sing a sequence. My heart leapt into my throat at the thought of singing in front of Piri—a daunting honour I could not refuse. With all the courage I had, I sang for the Oricha of honour that day, Oyá. No sooner had I gotten through the first line than my nerves dissipated. Eternal and beautiful, the song and rhythms carried me forward.

Masterfully crafted by Valdés and the drummers, the tambor progressed, increasing in energy and intensity. Then, one by one, the iyawós were led out and presented to Añá, each dressed in the clothing and colours of their Orichas. The congregation’s support for their spiritual journeys was tangible. Voices lifted, hands clapped, and they moved in time as a single, flowing body as the tambor reached its joyful climax. After a brief closing ceremony, it was all over. People lingered, chatting under the marquee, as if we had all just been to a village dance.

Portable Spirits: The Adaptability of Santería in Mexico

According to anthropologist Nahayeilli B. Juárez Huet, Santería is flourishing in Mexico due to the intersection of culture, politics, economics, communication technologies, migration, and tourism. Interest in Santería first emerged in Mexico during the 1940s and 1950s through music, cinema, and theatre—though often through racist stereotypes. Santería practice remained largely clandestine, as it was widely considered “witchcraft” in both Cuba and Mexico (Ortiz 2001; Juárez 2019:168).

The first Santería practitioners in Mexico were Cuban artists who emigrated during this period. Mexican involvement before the 1990s was rare, limited to middle or upper strata with U.S.–Cuba ties. Over the past twenty-five years, as practitioners have grown in number, this demographic has shifted. Oricha worship is now concentrated among poorer communities on the city’s outskirts (Juárez 2019b:24).

Santería is an imported spiritual practice rather than one rooted in the Afro-Mexican population, which makes up only 1.16 percent of the national population (Juárez 2019b:23). Juárez clarifies that Santería’s adaptability—with its “portable practices and symbols”—has allowed the practice to flourish in Mexico (2019b:23). López’s reasoning is more succinct: “Mexicans are believers.”

Mexican pre-Columbian Indigenous traditions, Catholicism (introduced by Spanish colonisers), Afro-Cuban spiritualities such as Santería and Palo Monte, and Santa Muerte (a new religious movement centred around the Mexican folk saint of death) are all spiritual systems that can merge, syncretise, and overlap without necessarily competing with one another. It is not uncommon for a believer to practice elements of all these traditions without feeling that they are compromising their faith (See Chesnut 2021:1 and Tavárez 2011).

On my first visit to Mexico City’s beautiful central Plaza de la Constitución, I witnessed a line of people—who looked like they were on their lunch break—waiting to be “cleansed” by Indigenous practitioners dressed in traditional attire. They used smoke, herbs, and incantations in a ritual that closely resembled a limpieza (spiritual cleansing) performed by priests of Santería.

The growing influx of Cubans and their culture into Mexico over the past decade has fuelled the expansion of Santería. To put this in context: in 2018, 492 Cubans presented themselves to immigration authorities; by 2023, the number had risen to 26,832 (Fresneda 2025:18).

But this is only part of the story. In 1985, Lázaro Cárdenas Batel—now Mexico’s chief of staff—helped bring the first tambor de fundamento to the country, giving voice to Añá in Mexico for the first time.

Cárdenas and the Birth of Añá in Mexico

Long before I had the opportunity to speak with Cárdenas directly, I had heard about him from several drummers, including López and his longtime friend, Cuban musician and batá drummer Juan Cisneros. They spoke of him with reverence—for his knowledge, his skill as a drummer and singer, and for the pivotal role he played in the emergence of the Mexican batá tradition.

Cárdenas hails from a prominent political lineage—his grandfather, President Lázaro Cárdenas del Río (1934–1940), is one of Mexico’s most revered leaders. He studied percussion at the Instituto Superior de Arte in Cuba, where he met his wife, Mayra Coffingy. After graduating in 1983, he returned to Mexico to study ethnohistory, graduating in 1987. He then began his political career, following in the footsteps of his father, Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, and became governor of Michoacán in 2002. In 2024, he was appointed Chief of the Office of the Presidency by President-elect Claudia Sheinbaum.

With a long-standing passion for Cuban culture, connections to Cuba’s drumming elite, initiation into the Añá drumming brotherhood, behind-the-scenes support for religious-musical education, and the advantage of relative wealth and a powerful family, Cárdenas was uniquely positioned to help bring Añá to Mexico. In April 2025, I spoke with him about his experiences and learned that the birth of Añá in Mexico had an auspicious start. The first Cuban drummers to bring fundamento and play in a ceremony in Mexico were legendary. The scene was first set in the late 1950s:

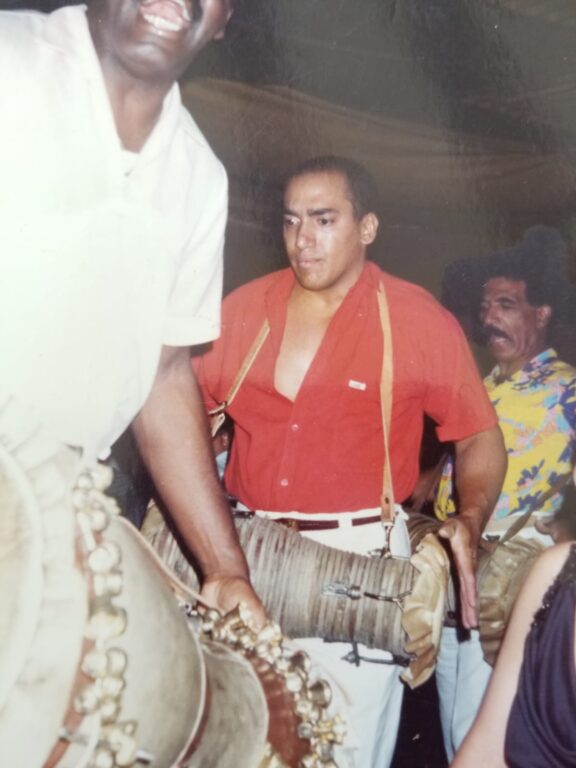

Jesús Pérez, Giraldo Rodríguez, and Gabino Fellove travelled to Mexico between 1959 and 1960 as part of a show, along with other Cuban artists. All three had been drummers for Pablo Roche. In Mexico, they recorded Afro Tambores Batá, a historic LP featuring singer Adriano Rodríguez, Giraldo’s brother and founder of the Cuban National Choir.

Jesús and Giraldo returned to Cuba. Gabino Fellove Valdés, “Ení Olá,” omó Agayú, remained in Mexico, where he died in the mid-1980s. He was the first omó Añá to settle in Mexico. However, he had neither students nor sufficient accompaniment to form a group of batá drummers. Since then, there have been a handful of practitioners of Afro-Cuban cults in Mexico, although not enough to sustain a group of drummers working regularly. Gabino, along with Silvestre Méndez, José Gárciga, and several other Cuban percussionists, worked in cabaret shows, playing popular music, performing various jobs, and occasionally playing güiro and bembé [other styles of religious musical drumming].

In 1984, Cárdenas heard that the Danza Nacional de Cuba planned a tour of Mexico–a troupe which featured his future wife, Mayra Coffingy and a group of elite drummers, including his mentor, Ángel Bolaños, and the legendary batá master Jesús Pérez. Cárdenas made a request, on behalf of several Mexican iyawós awaiting initiation, that Pérez bring his set of fundamento to Mexico to play at tambor. Pérez, who had spent time in Mexico between 1959 and 1960, agreed, and that year, fundamento batá were brought to and played in Mexico for the first time.

Pérez, also known as oba ilu (king of the drum), is iconic in the batá world. He was renowned not only for his playing but also for his advocacy of the protection of Afro-Cuban culture through performance and pedagogy (Miller 2003: 71). Some fifty years before playing Añá in Mexico, he gave one of the first-ever artistic presentations of batá music in Cuba, using aberikulá (non-consecrated batá) at Fernando Ortiz’s inaugural ethnographic conference on Afro-Cuban culture in 1936. This performance aimed to help a White Cuban audience learn about, appreciate, and stop fearing Black Cuban religion. The event had a resounding impact on the international dissemination of Cuban batá music—an influence that is still felt today, as batá rhythms and their cultural and spiritual significance continue to be replicated worldwide.

The first tambor de fundamento in Mexico was played at the home of Margarita de la O, a Cuban santera and daughter of the Oricha Yemayá, who lived in Mexico. The drummers who performed at the ritual were all those on tour with the Danza Nacional de Cuba at the time, including Ángel Bolaños, Regino Jiménez, Armando Aballí, and Orestes Berríos, as well as Cárdenas and Gabino Fellove, who had settled in Mexico. Other luminaries who attended this historic event, according to Cárdenas, were:

Orestes Suárez “Papi,” a great akpón and güirero. Other members of the Danza Nacional participated, among them Nancy Rodríguez, Inés María Carbonell, and Ricardo Gómez Santacruz. In addition, a group of Cubans living in Mexico were at Margarita’s home, including Francisco Fellove, Gabino’s brother and a great Cuban popular music singer; world boxing champion Ultiminio Ramos; and his sisters Arlette and Guendolina, members of a very traditional and respected family from Matanzas; Orlando “Bebo” Rodríguez, santero; singer Olga Guillot; actress Ninón Sevilla; and Silvestre Méndez, rumbero and composer, among others.

In 1985, at the age of seventy, Pérez passed away. Yet his legacy endured, and three decades later in Mexico, it gave rise to a profound spiritual and musical movement. A year after his death, the Danza Nacional de Cuba toured in Mexico again. This time, they brought Aña Okó Bi Ayé, a very old and well-respected tambor that originally belonged to Alejandro Adofó. Several tambores were played at Bebo’s house.

Video courtesy of Chris Walker. El Nopal Centenario, Tijuana, B.C. México, 1989 Singers: Lázaro Ros Coro: Orestes Berrios, Juan Cisneros Drummers: Iyá – Mario Jáuregui, Itótele – Regino Jiménez Saez, Okónkolo – Lázaro Cárdenas Batel. Dancers – Ricardo “Windo” Jáuregui, Margarita Ugarte.

Another crucial element in the development of the batá tradition in Mexico was the introduction of an educational program on Afro-Cuban drumming, song, and dance, which Cárdenas helped establish between 1987 and 1988. These workshops continued for three or four consecutive years in universities and cultural centres in Mexico City, Jalapa, and Tijuana. They fed directly into the religious milieu of Mexican society.

Cárdenas reflects on those who were present at this time and on the significant impact of their contributions in Mexico and beyond.

Regino Jiménez, Orestes Berrios, Julio Guerra, Mario Jáuregui, Ricardo Jáuregui “Windo,” Miguel Valdés Aballí, Cristóbal Guerra, Roberto Vizcaíno, and Juan Cisneros participated in those workshops, along with singers Felipe Alfonso, Lázaro Ros, and Juan de Dios Ramos. In this context, the drums of Adofó and Jesús Pérez returned to Mexico a couple of times.

In Mexico, Ángel Bolaños and Mario Jáuregui were the most influential drummers in the early days. Bolaños for his deep knowledge of Añá, both musically and ritually. Mario, for his part, spent long periods in Mexico and had many students, both in Mexico City and in Jalapa, Veracruz.

It is also important to note that, during his time in Mexico, Regino Jiménez became a teacher for great California percussionists, such as Michael Spiro, Mark Lamson, and Chris Walker “El Flaco,” among others. During those years, Mark and Chris spent extended periods in Mexico, participating in Afro-Cuban percussion workshops and also playing fundamento.

During this period, strained U.S.–Cuba relations made it difficult for North American citizens to travel to the island. Mexico thus became a nexus of cultural, religious, and musical exchange: Cubans shared their knowledge, while interlocutors from Mexico and beyond spread the word, fuelling exponential interest in the religion and its music.

The next significant stage occurred in the early 1990s, when two sets of Añá were brought to Mexico to live. One belonged to Luis Valdés, who was born in Cuba in 1960 and raised in Miami. He studied with and was sworn (initiated) to Añá in Miami by Pipo Peña, who, incidentally, is believed to have consecrated the first set of Añá on U.S. soil in 1975. He also played alongside Juan “El Negro” Raymat before moving to Mexico City in 1987. He recounts:

When I got to Mexico, there was no [religious] music. I went to Mercado Sonora — a huge religious market in Mexico City — and there was no Santería paraphernalia, nothing. Just limpiezas with leaves and local spiritual customs. I bought some güiros and made my own instruments. Then I hired Roberto Agüero, who had arrived with Enrique Horín’s group — a very famous bass player — and I initiated him to Shangó. I sat on the conga, my brother sang, and we played the first güiro [musical religious ceremony using non-consecrated instruments]. There must have been 300 people there. I thought, “Wow, what is this?” No one was initiated, but they were all amazed.

In 1994, Valdés brought Mexico’s first set of Añá from Cuba, called Añá Shango Ade, officially consecrated on 22 March 1994 and “born” from Isidrito’s drums, Añá Obanikoso. Valdés explained that when the Conjunto Folklórico Nacional de Cuba later arrived with consecrated batá, ceremonies became very exclusive — only for a select group within a certain circle. Valdés’ drums, however, were of the people, serving Mexico’s growing religious community.

Although he never made his living from drumming, his fundamento worked every weekend. He told me that in the beginning, there were so many iyawós needing presentation that the ritual musicians grew tired of repeating the required song and drum sequences, so they began limiting presentations to six or seven per ceremony.

Valdés was instrumental in teaching batá to the first generation of professional Mexican players, with Óscar Méndez and his brother Paolo among his earliest students. A few years later, when the Méndez brothers brought their own set of Añá to Mexico, “all of a sudden everybody went for drumming — and it’s still going,” he said.

The second set of Añá was brought from Cuba by Cárdenas in 1995—the same year he became an omó Añá. Unlike Valdez’s set of fundamento, Cárdenas’s drums were not played in the wider religious community. I was intrigued to know if this had something to do with Cárdenas’s political career—especially considering the negative press linking Santería with Mexico’s criminal underworld. He explained that,

There is still a lot of prejudice because of a lack of deeper knowledge of the origin of the culture and the root behind all of this. It is seen in many other parts as magic, superstition or practices like that of witchcraft […] I got close to this because of a cultural interest, because of an interest in music and because I was also studying anthropology, so I didn’t come to this through religion, to put it that way.

When I inquired whether Cárdenas had been clandestine about his beliefs and practices because of his political aspirations, he replied,

It’s not a secret, but I haven’t mixed it up [politics and religion]. It’s true that when I was a candidate running for governor of Michoacán, yes, there were some negative campaigns saying that if I became governor, Santería would be officialised in Michoacán, stupid things like that.

I came across several media reports discussing Cárdenas’s religious beliefs. One of them, Razacero, a Mexican digital publication known for its critical stance toward the political establishments, said of Cárdenas, when he secured the governorship of Michoacán in 2002,

[P]olitically speaking, he had no real merit to justify holding such a position. His main skills at the time (and arguably still today) were playing percussion instruments and practising Cuban Santería—hardly credentials for leading a Mexican state.” (Razacero 2023, see also “El servilismo de Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas” 2014, Becerril 2001, Moctezuma de León 2024)

Twenty-three years later, Cárdenas’s rise to Chief of Staff makes clear that his interest in percussion and Cuban Santería was far from his only qualification for office.

Present-Day Añá in Mexico

Despite the favourable beginnings of Añá in Mexico, Méndez, López, Cisneros, and Miniconi all admit that musical and ritual knowledge was, until recently, limited and somewhat cobbled together. It is only in the last fifteen years, following the influence of key Cuban drummers living in Mexico who have shared their knowledge, that Añá and the batá tradition have matured—evolving into a fully-fledged musical-ritual practice that stands on its own two feet.

As López puts it, “If all the Cubans left Mexico tomorrow, the religion would continue without them.” Cárdenas clarifies:

Mexico has been fortunate to permanently enjoy the presence and contributions of great Cuban omó Añá: Piri, Yumey, Alexis, Vladimir, Lekiam, Alexander, Damiani… It can be said that, with all of them, as well as with the older omó Añá from Danza Nacional and the Conjunto Folklórico Nacional, Mexico has received the best of Cuba. This has allowed to build a community of batá drummers in Mexico as strong and solid as those found in New York or Miami.

Recently, this community has been enriched by the arrival of talented Matanceros such as Orlandito “el Yamba,” Yosvany Oliver, Albertico Puñales, and the singer Yaíma Pelladito, among others. Prominent Mexican drummers have become maestros over the years: “Los Niños,” Miguel Carlón, Nereo [Herrera], Miguelito Cruz, Dionisio Alzaga, and others. I won’t mention them individually to avoid omissions.

In my opinion, there are two remarkable teachers, two elite drummers who have left a profound mark and have the merit of having established a school in Mexico. In the early years, Mario Jáuregui “Aspirina,” and more recently, Manley López “Piri.” For the record, Piri was sworn in Añá by Pedrito “Aspirina”. Their families, the “Chinitos” and the “Aspirina,” have very strong ties. That is, even though we are talking about two distinct moments and contexts in the development of the drum, there is coherence and continuity; they share the same origins and a common original school.

Two brothers, known as Los Niños (“The Boys”), were repeatedly mentioned as key progenitors of the Mexican batá tradition during my research in Mexico. Óscar Méndez was six years old when he and his older brother, Paolo, earned their first pesos playing at a tambor—making them possibly the youngest Mexicans to play batá at that time. They were taught by their uncle, Juan Jiménez, who, according to Cárdenas, was one of the Mexican students who attended the Cuban batá courses in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

We were warmly welcomed into Óscar Méndez’s spacious, well-appointed apartment. He was prepared for us: several boxes of videocassettes, dating back decades, had been pulled out of storage and dusted off. Each cassette—filled with footage of tambors—offered a dense visual history of batá music in both Mexico and Cuba. Clearly a collector and historian, Méndez proudly guided us through the videos, many of which featured familiar figures and friends from the Cuban drumming dynasty.

From their humble beginnings, the brothers would go on to preside over a batá empire. Los Niños can have up to six sets of Añá playing simultaneously in different locations and average around fifteen ceremonies a week.

“Right now, in Mexico, you can make a living off the tambor,” Méndez clarifies. “And you can earn a lot more than someone with a college degree.” However, he adds, “A lot of depth has been lost. Many say it’s just a trend, a money thing, a business, a lifestyle. But it wasn’t like that before. There used to be a lot of rules and a lot of respect.”

López explained that a professional batá drummer can earn enough to survive with just two or three ceremonies a week—if you don’t have a family and share rented accommodation. This is not the case in Cuba, which is experiencing an economic downturn, resulting in a talent drain as many Cuban drummers move to Mexico. As a result, according to López, there are now hundreds of sworn ritual batá drummers earning a living by playing in ceremonies across Mexico City—a number that has doubled since he arrived thirteen years ago.

“Los Niños,” Óscar and Paulo Méndez, Ruben Bulnes, David Pattman and others at a Santería ceremony in Mexico City: 6th February 2025. Video by Vicky Jassey.

Playing for Power: Tambor de Fundamento, Animal Sacrifice, and the Mexican Underworld

Whilst most Santería rituals—including the batá canon—have been copied from Cuban practice and transplanted onto the Mexican socio-religious landscape intact, there are exceptions. One example is the unique way Santería intersects with, and is interpreted and expressed through, its integration with Mexican Indigenous and/or modern spiritual influences, such as Santa Muerte. Another, more extreme, example is how it has been adopted by Mexico’s criminal underworld in the pursuit of power and protection.

It was challenging to include the following examples because, if they are taken out of context and inflated to represent Santería as a whole rather than a minority practice, they will reinforce problematic stereotypes. Yet leaving them out would be a failure to tell the whole story. So, here are several testimonies from Mexican drummers that reveal the dangerous—and at times extreme—realities faced by batá drummers working in Mexico.

(The authors below gave explicit permission to use their names and fully understood the implications of their stories being published.)

Dionisio Alzaga: Tecamac 2010

They told us we were heading to a place called Tecamac in the State of Mexico. When we got there, it looked just like any regular building until we heard a lion roar. We went in, and the place was full of cages built out of concrete. The place was specifically designed as a breeding ground. I don’t remember the exact number, but there were two tigers, a black puma, and I think, if I’m not mistaken, there was a jaguar, too. They were all in separate cages. The only big one was a huge cage where a lion was kept with five lionesses. I guess that was the one they were using for breeding at the time.

We heard about five gunshots. The ritual was happening, and we were already there, so we couldn’t really leave. By the time we went back in, they had already taken the [dead] lion out of its cage and started hanging it from a tree. I couldn’t tell if the ceremony was for a politician or an artist. But it was definitely someone with money because they said one of those lions cost around 80,000 pesos, which at that time would be like $6,000.

They told us to start playing, meanwhile they started skinning the lion and brought in the guy who was paying for the sacrifice, they laid him down and bathed him in the lion’s blood.

As soon as we’d finished, we grabbed our stuff and left. Honestly, we never thought we’d see a ritual like that, I mean, in Cuba, you’d never see someone sacrifice a lion, right? It was just really shocking for all of us.

Alzaga’s experience was not an isolated occurrence. Miniconi recounted playing at a tambor de fundamento where he saw a young lion, the size of a large dog, which he believed was drugged and waiting to be sacrificed to the Oricha Chango, but Miniconi didn’t stay to see it. Méndez recounted:

The first thing I want to say is that it’s all about positions. It’s a war. It’s a battle of power. I saw that once [a lion sacrificed], but that was the first and last time. On the second occasion, when they said they were going to sacrifice a lion for Chango or Orula, I said no. When I asked them why they would do that, they told me, ‘My godchild is in the American mafia and needs religious work done to save his life.’ It is this that has sullied it [the religion].

The topic of blood sacrifice is a delicate subject that deserves more attention than this article can offer. However, to provide some context: in Cuba, blood sacrifice typically involves chickens and pigeons and, less frequently, pigs, goats, sheep, or turtles. In Santería, blood sacrifice is a vital ritual that channels aché—the sacred life force—to the Oricha (deities). Blood, believed to carry concentrated spiritual energy, strengthens the bond between practitioners and the divine. Sacrifices are offered to express gratitude, seek healing and cleansing and provide protection against danger, misfortune, illness, or spiritual attack. The meat is often shared among the community afterwards, except when the ritual serves as an ebó (a cleansing ceremony).

Animal sacrifice plays a central role in initiation ceremonies, symbolising the transfer of aché and deepening the devotee’s connection to their Oricha. However, the ritual sacrifice of large game takes this idea to an extreme new level and plays into problematic historical stereotypes promoted by White-Christian institutions that have historically depicted African diasporic religions as primitive, satanic, and threatening. Often, these practices have been misrepresented and weaponised to support racist narratives. Yet animal sacrifice and animal cruelty, although they do not necessarily go together, are not unique to Oricha worship; it continues today in Islam and Hinduism and was a central practice in ancient Jewish, Christian, and Greek traditions. Meanwhile, in Europe and parts of America, in the name of tradition, pain, fear and death are regularly inflicted on bulls for entertainment, and such practices are normalised.

It is possible that lion sacrifice—along with the use of Santería as a tool for protecting criminals and mafia figures—reflected a particular phase in the religion’s development in Mexico. The drummers I interviewed who are currently active in Mexico, such as López, Herrera, and Cisneros, did not report incidents of large game being sacrificed.

Since 2024, Mexico’s Senate has improved the chance for animal welfare by approving historic legislation, which aims to:

[P]rotect animals, guarantee their wellbeing, provide them attention, good treatment, maintenance, accommodation, natural development, health and avoiding abuse, cruelty, suffering, zoophilia and the deformation of their physical characteristics, as well as ensuring the animal health. (Staff 2024, “Por unanimidad, La Cámara de Diputados Aprobó reformas” 2024)

Although the bill now prohibits animal sacrifice for religious purposes, Méndez explained that, in practice, priests continue these rituals behind closed doors—and, to date, no one he knows has faced prosecution.

The clash between religious freedom and animal protection has long been a point of legal debate in the United States, most notably in the Supreme Court case Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520 (1993). In this case, the Court struck down laws that specifically targeted Santería but affirmed that neutral, broadly applicable legislation—such as animal cruelty statutes—may still be enforced as long as they are not intended to suppress religious expression.

In addition, there has been a flood of media coverage that equates Santería with drug trafficking. The most infamous case came in 1989, when Mexican authorities uncovered evidence of ritual human sacrifices tied to the drug trade operating on a ranch near the U.S. border. Adolfo de Jesús Constanzo, a Cuban American drug trafficker and Palo practitioner, was killed during the police raid, but several of his followers were tried and convicted. There is no credible evidence that Constanzo was a formal practitioner of Santería, but in the popular Mexican imagination, “Santería” was tainted.

While not all smoke means fire, there are reports of Santeria being used as a form of protection for those involved in, or connected to, violent crime. For example, Méndez recounted playing at a ceremony where the so-called iyawo was someone who had been kidnapped. The following day, he found out that everyone at the ceremony had been arrested. During another ceremony, a gun was pointed at him, and his car was smashed up after the padrino (religious godfather) officiating the tambor took a dislike to two of his friends.

We’ve had to go to other states in Mexico where we have driven up roads lined with people holding guns,” he continued. “Then they put a dark hood over us. Super crazy. Like something out of a Netflix show. But with drums!”

*****

The story of Añá in Mexico is one of migration, resilience, adaptation, and contradiction. What began as a modest cultural-religious transplant has evolved into a powerful musical and spiritual force, shaped by the contributions of Cuban and Mexican drummers, devoted practitioners, and influential figures. Through their voices, we hear Añá echo across the country’s religious landscape—simultaneously preserving and transforming Afro-Cuban traditions as they are woven into local spiritual, cultural, and economic realities, fuelling Santería’s rapid rise in Mexico in recent years. While stories of criminal exploitation have threatened to taint its image, these coexist with a deeper and more abiding truth: one of devotion, artistic excellence, and community.

This article was updated on December 1, 2025, to include the account and photo from Luis Valdés.

A special thanks goes to Antoine Miniconi, “Piri” López, and Oscar Méndez for their generosity during our time in Mexico. I am also deeply grateful to Lázaro Cárdenas for taking the time to speak with me, as well as to all the musicians listed in the Personal Communications section who shared their time and experiences. I am especially grateful to David Pattman for his support throughout this project, including accompanying me to all the interviews and assisting with translations. My heartfelt thanks also go to Elisa Hough and Amalia Cordova at the Smithsonian, as well as to Hannah Beardon, Jessamy Boydell, and Juliana Ruhfus.

Bibliography

Personal Communications

Alzaga Cortés, Dionisio. Personal communication. April 21, 2025.

Cineros Bello, Juan Ángel. Personal communication. February 6, 2025.

Cárdenas Batel, Lázaro. Personal communication. April 21 & 24, 2025.

Herrera González, Nereo Ángel. Personal communication. January 26, 2025.

López “Piri,” Manley. Personal communication. February 1, 2025.

Miniconi, Antoine. Personal communication. February 5, 2015.

Méndez Jiménez, Oscar Miguel. Personal communication. February 4, 2025.

Books and Academic Articles

Castillo Terán, Gabriela. “A Mexican Religion: Marian Trinitarian Spiritualism.” Religión y Relaciones Internacionales Contemporáneas 1 (2010): 301–310.

Kingsbury, Kate, and R. Andrew Chesnut. 2021. “Syncretic Santa Muerte: Holy Death and Religious Bricolage.” Religions 12 (3): 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12030220

Edel J. Fresneda, “Cuban Migration as A Transnational Vulnerability Dispersion,” Iberoamericana – Nordic Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies 54, no. 1 (2025): 11–21, https://doi.org/10.16993/iberoamericana.685.

Hagedorn, Katherine J. Divine Utterances: The Performance of Afro-Cuban Santería. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 2001.

Juárez Huet, Nahayeilli B. Santería en México: Trayectorias transnacionales de la religiosidad afrocubana. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2019.

Juárez Huet, Nahayeilli B. 2019b. “Dos narizones no se pueden besar: Raza, cuerpo y nación en la práctica de la santería afrocubana en México.” Alteridades 29, no. 57: 109–118. https://www.cephcis.unam.mx/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/24-dos-narizones.pdf.

Miller, Ivor. “Jesús Pérez and the Transculturation of the Cuban Batá Drum.” Diálogo 7, no. 1 (2003). https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol7/iss1/14.

Ortiz, Fernando. Los negros brujos. 1906. Reprint, Miami: Ediciones Universal, 1973.

Tavárez, David. The Invisible War: Indigenous Devotions, Discipline, and Dissent in Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011.

Online Sources

Becerril, Andrea. “Lázaro Cárdenas Batel Niega Prácticas de Santería; Acusa Campaña Sucia.” La Jornada. September 27, 2001. https://www.jornada.com.mx/2001/09/27/013n1pol.html.

Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah, 508 U.S. 520 (1993).

Contralínea. Cepeda Neri, Álvaro. “Gil Olmos y los brujos del poder.” January 11, 2015. https://contralinea.com.mx/exlibris/gil-olmos-los-brujos-del-poder/.

Cámara de Diputados. “Por unanimidad, La Cámara de Diputados Aprobó reformas a la constitución para prohibir el maltrato a Los Animales.” Comunicación Social. November 12, 2024. https://comunicacionsocial.diputados.gob.mx/index.php/boletines/por-unanimidad-la-camara-de-diputados-aprobo-reformas-a-la-constitucion-para-prohibir-el-maltrato-a-los-animales.

El Universal. “Tras caso de bebé muerto en penal, Barbosa cambia a responsable de cárceles de Puebla.” https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/estados/tras-caso-de-bebe-muerto-en-penal-barbosa-cambia-responsable-de-carceles-de-puebla/.

Grupo Milenio. “Hallan altar satánico y drogas tras cateo en la GAM.” Milenio. April 17, 2024. https://www.milenio.com/policia/hallan-altar-satanico-drogas-cateo-gam.

Mexico News Daily. “Senate Passes Legislation That Enshrines Animal Welfare in Constitution.” November 26, 2024. https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/animal-protection-legislation-to-punish-abuse-in-mexico/.

Milenio. “Senado aprueba reformas en materia de protección animal.” April 25, 2024. https://www.milenio.com/politica/senado-aprueba-reformas-materia-proteccion-animal.

Moctezuma de León, Héctor. “¿Un santero en Palacio?” Índice Político. July 16, 2024. https://indicepolitico.com/un-santero-en-palacio/.

Razacero. “¿Un santero en la Presidencia?” 2023. https://www.razacero.com/?p=24729.

ResearchGate. “Los narcosatánicos de México.” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348415997_Los_narcosatanicos_de_Mexico/citation/download.

Staff, M. N. D. “Senate Passes Legislation That Enshrines Animal Welfare in Constitution.” Mexico News Daily. November 26, 2024. https://mexiconewsdaily.com/news/animal-protection-legislation-to-punish-abuse-in-mexico/.

“El servilismo de Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas: ¿Fracaso o éxito de la ‘izquierda’ mexicana?’ Periódico Razacero. August 17, 2014. https://razacero.com/?p=1953.

“Por unanimidad, La Cámara de Diputados Aprobó reformas a la constitución para prohibir el maltrato a Los Animales.” Comunicación. November 12, 2024. https://comunicacionsocial.diputados.gob.mx/index.php/boletines/por-unanimidad-la-camara-de-diputados-aprobo-reformas-a-la-constitucion-para-prohibir-el-maltrato-a-los-animales.

Glossary of Santería Terms

Aberikulá – Unconsecrated batá drums. Aché – Life force or spiritual energy.

Akpón – Lead singer in Santería ceremonies who guides the musical invocation of Oricha.

Añá – Yoruba deity believed to reside inside consecrated batá drums, enabling communication with Oricha during rituals.

Babalawo – High priest in Santería, usually responsible for divination and leading rituals.

Batá – Consecrated double-headed drums used in Santería rituals to invoke Oricha.

Ebó – Sacrificial offering.

Fundamento – The consecrated set of batá drums believed to contain the spirit of Añá.

Iyawó – New initiate in Santería undergoing a period of spiritual development and ceremonial rites.

OmóAñá – Initiated male drummers dedicated to Añá and responsible for ritual music in Santería.

Oricha – Deities in the Santería religion with whom practitioners communicate through drumming and rituals.

Oru cantado – Sung sequence in Santería ceremonies that accompanies drumming to praise and call Oricha.

Oru seco – Drum-only sequence in Santería performed before singing begins.

Padrino – Spiritual godfather who mentors new initiates in Santería.

Palo Mayombe – Afro-Cuban religion derived from Central African traditions, distinct from Santería.

Santa Muerte – Mexican folk saint associated with death, worshiped in a distinct syncretic religious tradition.

Santería – Afro-Cuban spiritual practice derived from Yoruba Oricha worship.

Tambor de fundamento – Ritual event featuring consecrated batá drums.